Short book reviews by Jacob Williams from 2020. Send feedback to jacob@brokensandals.net.

All Systems Red by Martha Wells (2020-12-31)

The name of the series made me very skeptical that this would be the kind of thing I'd enjoy, but that was misguided. It's a very fun story.

The Midnight Library by Matt Haig (2020-12-30)

How should this book be categorized? It includes a little quantum handwaving so that it can pass for sci-fi, but not much would have been lost if that had been dropped and the library had been left unexplained. One of my favorite authors, Ursula Le Guin, described some of her stories as "psychomyths," and I think that term is apt here too. This book isn't really about the Library, or Nora, or Nora's lives; it's meant to be about every person's life. It's meant to convince you that life is worth living and worth being excited about.

You can tell it's probably going that direction from early on, so it's no surprise that Nora decides to return to her original life - what other conclusion would allow the story to have any relevance for us in the real world? So the success of the novel depends on how good the writing is along the way (it's good) and on how compelling the message is. Let's talk about the latter.

The story suggests a few different sources for Nora's despair. A minor one is her feeling that "she didn't deserve to be happy". I can't identify with this, since most of the time I just don't think in terms of people "deserving" or "not deserving" things. But it seems to come up a lot in fiction so I guess it's something people struggle with.

A bigger focus is Nora's regrets over missed opportunities. Sometimes people seek solace over regrets by elevating a "sour grapes" mindset into a whole worldview, imagining that any other path they'd taken would be just as bad in its own way as their actual life. If you were a rock star you'd be tormented by the fame, if you got your dream job your family life would suffer, etc. The book resists fully taking this approach, thankfully, but it does have some tendencies in that direction, and those elements aren't my favorite. But I did find this bit thought-provoking:

Weirdly, she felt just as sad for the version of her who had never fallen in love with the simple beauty of Thoreau’s Walden, or the stoical Meditations of Marcus Aurelius, as she had felt sympathy for the version of her who never fulfilled her Olympic potential.

Anyway, I think Haig is more concerned to convince you that no matter what you're missing out on, plenty of great possibilities remain open to you:

...most of what we’d feel in any life is still available. We don’t have to play every game to know what winning feels like. We don’t have to hear every piece of music in the world to understand music. We don’t have to have tried every variety of grape from every vineyard to know the pleasure of wine. Love and laughter and fear and pain are universal currencies.

Well, maybe. Quantities matter, though, and in particular the proportioning of "love", "fear", and "pain" given to each person seems to vary widely. Someone whose life is routinely weighted toward the latter may understandably worry that they're stuck in an existence that's just not worth it. Nora realizes that "she had managed to convince herself that there was no way out of her misery" - it's a natural conclusion to reach if you have years of experience of not actually finding a way out of your misery.

Hope depends on believing there are options you haven't yet explored. And this is the message of the book that resonates with me most: our options are innumerable. We can't access alternative versions of the present, and countless futures are already closed off, but an infinite number of futures are still open to us too. The thrill of the multiverse is available in every moment.

She just needed potential. And she was nothing if not potential. She wondered why she had never seen it before.

The End of Night by Paul Bogard (2020-12-30)

...while the humans are home in our boxes watching our boxes, the nocturnal creatures keep this world alive.

If I had simply sat down to read this, I probably would've found it dreadfully boring. But instead, I listened to the audiobook while walking around the city - being a noctambule, as Bogard might say - and it set a perfect, meditative mood. And it has certainly heightened my awareness of how little darkness I actually get to experience; it's inspired me to keep the lights off more at night and rely on some relatively dim red nightlights when possible.

I'm suspicious as to whether some of the scientific claims are adequately supported, particularly the insinuation that we should be worried about light at night causing cancer, but I didn't care enough to research it further (since I'm already on board with the basic thesis that reducing light pollution is desirable).

The Hidden Girl and Other Stories by Ken Liu (2020-12-19)

Parents fear to be forgotten, to not be understood by their children.

This is a pretty uneven collection. Several of the stories try to inspire the sense of wonder associated with legendary events and larger-than-life heroes, which mostly falls flat. But some of the others I really enjoyed:

- "Staying Behind", which highlights how radically one's philosophical views would affect one's perception of a singularity scenario;

- "The Reborn", a neat thought experiment on personal identity and accountability;

- "Memories of My Mother", a very short but moving story.

Eleanor Oliphant Is Completely Fine by Gail Honeyman (2020-12-15)

I tend to empathize a little too much with characters embarrassing themselves, which made this book very difficult to read. But it was worth pushing through to the end. This is a really authentic and moving examination of loneliness and the experience of being ignorant of social customs.

Ink & Sigil by Kevin Hearne (2020-12-12)

A very fun, light story.

An Autobiography by Mahatma Gandhi (2020-12-11)

The seeker after truth should be humbler than the dust.

I knew very little about Gandhi before beginning to listen to this, and since it ends before covering much of his involvement in the movement for India's independence, I'm still fairly ignorant. What's most endearing and inspiring about Gandhi as he presents himself here, though, is his implacability in adhering to his conscience. From writing a confession to his father as a child, to asking a judge to throw out his own case as an adult, Gandhi sets an example of submitting oneself to the demands of morality, even when it is personally costly or humiliating.

Less appealing is his obsession with self-restraint. The religious impulse to see pleasure as inherently problematic, and to seek purity through self-denial, is a recurring theme in his life. His diet, for example, is continually shrinking, and he seems to view any enjoyment of food as a sort of moral failure. I think this is misguided, but it's hard to avoid seeing a connection between such self-discipline and the strength of will that enabled him to become so influential.

I listened to the audio version narrated by Sagar Arya, which I recommend.

The Wind's Twelve Quarters by Ursula K. Le Guin (2020-12-01)

A youth who bore mid snow and ice a banner with this strange device HELP HELP I AM A PRISONER OF THE HIGHER REALITY.

Apart from the classic parable "The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas", I don't think this collection contains anything nearly as memorable as my favorite Le Guin novels (The Dispossed and The Lathe of Heaven). Many of the stories are pretty good, but rarely gripping; it took me a long time to get through all of them, despite the book not being particularly long. My favorite here is probably "Vaster than Empires and More Slow", and "The Field of Vision" is an interesting premise as well.

The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume One, 1929-1964 (2020-11-15)

I bought this perhaps 15 years ago. It's traveled a couple thousand miles with me and gone through the cycle of unpacking, shelving, and packing again across half a dozen homes, serving mostly as decoration - a totem proclaiming my love of sci-fi. I didn't actually read much of it until this year.

If someone perusing my shelf during that period had selected this and opened it at random, the prose would not have reflected well on my taste. Most of these stories do their part to justify one or more of the negative stereotypes associated with science fiction, in particular poor dialogue and excessive exposition. They also provide stark reminders of how radically cultural attitudes toward gender have changed in the past century: the recurring assumption that leadership, space exploration, and pretty much any serious occupation are roles to be filled only by men is possibly more jarring than the outdated science and technology.

Slightly more subtle but equally uncomfortable is the fixation on race that you see in a lot of these stories. It may be the race of "Man", not particular subgroups of humans, that is the object of reverence for many of these authors, but that reverence is still unsettling. There's a sort of romanticization of a race achieving its destiny, fighting for its place among others, dominating nature; one often suspects the same sort of thinking that undergirded 20th century racist aggression has just been uncritically transposed into a setting where species are substituted for races.

Nonetheless, there's a lot to like here. Presumably I read the classic "Flowers for Algernon" as a child, but my memories of it were, let's say, somewhat hazy (spoiler: it is not about a mouse that achieves human-level intelligence). It was definitely worth revisiting, and probably is the best story in the collection. Some other highlights:

- the memorable images of the endings of "Nightfall" and "The Nine Billion Names of God"

- Zelazny's delightful writing in "A Rose for Ecclesiastes", which makes me want to read more of his work

- the juxtaposition of two perspectives on a nearly-utopian world in "The Country of the Kind"

- the poignant premise of "The Cold Equations", albeit marred by sexism and some repetitiveness

Blood Child, and Other Stories by Octavia E. Butler (2020-11-07)

If we’re not your animals, if these are adult things, accept the risk. There is risk ... in dealing with a partner.

I think the titular story is the highlight of this collection, but out of the seven stories and two essays I'd say only two are misses. "Crossover" is a gloomy slice-of-life that is just too vague for me to connect with. "The Book of Martha" is all about how difficult it would be to create a utopian world even with omnipotence, an assumption that seems wildly implausible to me.

Mexican Gothic by Silvia Moreno-Garcia (2020-10-31)

Suffers a little from some sudden exposition dumps, but otherwise a great horror story.

Meditations by Marcus Aurelius, Gregory Hays translation (2020-10-28)

When you wake up in the morning, tell yourself: The people I deal with today will be meddling, ungrateful, arrogant, dishonest, jealous, and surly. They are like this because they can’t tell good from evil. But I have seen the beauty of good, and the ugliness of evil, and have recognized that the wrongdoer has a nature related to my own...

Much of the appeal of this book for me lies in the supposition that it was never meant to be published. It's a chance to see the unfiltered personal thoughts of a ruler. Despite the eighteen centuries and many social strata separating me from Aurelius, the subjects that occupy his mind seem entirely relatable. Is the universe fundamentally orderly, or random, and what does the answer mean for us? How should we deal with people who frustrate us or misbehave? How can we come to terms with death?

His answers are often influenced by implausible assumptions. He believes that the universe as a whole is perfect; that whatever is natural is, ultimately, good. He also seems to believe we have absolute control over our own minds. Both of these reflect the common human tendency to try to convince ourselves there's nothing fundamentally or irreparably wrong with the world; that suffering is always either somehow good, or within our power to escape. I don't think either of those is true.

But a solution doesn't have to be 100% effective in order to be valuable. Stoicism provides potentially useful tools for coping with unalterable circumstances, and Aurelius's presentation of it is inspirational.

An Unkindness of Ghosts by Rivers Solomon (2020-10-20)

She was standing on the edge of a new world and so ready to jump. How Lucifer felt upon leaving the Heavens. He didn’t fall. He dove.

Great characterization (at least of the protagonists; the villains are one-dimensional) and a plot that's gripping, if sometimes forced.

Waking Up by Sam Harris (2020-10-13)

I'm still not a huge fan of the term "spirituality", but this at least helps me better understand why some nonreligious people would choose to use it. More importantly, this book is a pretty compelling sales pitch for meditation. Harris presents it not as a permanent panacea but, perhaps, as a panacea that's available to use for a few minutes at a time, which is certainly something I'd like to have available to me.

An important claim underlying the book is that the self is an illusion. Interpreted in a certain way, that claim would obviously be false; I'm writing this comment, so clearly I have no trouble using the word 'I' to refer to something that exists. A better way to interpret it is that there is no persistent, clearly delineated entity that exists across time and corresponds to 'me'. I think the kinds of thought experiments and psychological data that Harris mentions provide strong reasons to believe there is no such entity. Still, even if that claim is rejected, the book's point that we know it is possible to experience certain desirable conscious states that are not part of our everyday experience, and that it's worth exploring whether certain spiritual traditions have managed to develop techniques for inducing them (even if their understanding of why those techniques work is misguided), seems reasonable.

Daydreams of Angels by Heather O'Neill (2020-10-11)

We think these are our own thoughts, but they are not. They are like frozen-dinner thoughts. We buy them already made and then heat them up in our brains a little and then think them. As if they are our own. As if thoughts didn't take any effort.

There are two things I love about O'Neill's writing. One, the eloquent metaphors. ("Parents go through their children's psyches looking for contraband ideas the way that guards toss apart prisoners' cells looking for items that they might have smuggled in.") Two, the delightful little absurdities sprinkled throughout. ("A French philosopher had composed a text so difficult that no one had even been able to get through the title.")

The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank (2020-10-08)

This diary is truly a priceless artifact.

The hardships of life in the Secret Annex bring many questions to the fore, but two are of particular interest to me: how do we go on in the face of extreme suffering? And is it worth it to try?

To the first question, Anne's mother suggests keeping in mind that others are in even worse circumstances than they are. When this advice is given today, circumstances such as Anne's are often precisely what we have in mind as being "even worse". I've never found much comfort in this, and neither did Anne. She believed, rather, that we must focus on the good, and especially the beauty of the natural world. She seems also to have kept herself busy with projects and plans, and found hope in the development of an intimate relationship.

My second question is perhaps unanswerable. Anne wrote once, after nearly two years in confinement: "Let the end come, however cruel; at least then we'll know whether we are to be the victors or the vanquished." But the end was still about nine months away when she wrote that--nine more months of depredation, only to learn she would indeed be among the vanquished. History has vindicated her, and in a certain sense made her the victor: her dream of being a successful writer has been achieved beyond what she could ever have guessed, and she's been an inspiration to millions. Would she think it was worth it? Or if she'd known how her life would end, would she have preferred to die at the outset? I wish I could ask her.

I'll Be Gone in the Dark by Michelle McNamara (2020-10-06)

I probably should have gone for text instead of the audiobook. It's narrated well but, with so much jumping around in time and between different people's stories, it's easy to feel lost quickly if you aren't giving it your full attention.

Stephen Hawking by Leonard Mlodinow (2020-09-27)

Some reviewers complained that the details about Hawking's physical condition were TMI. But that sort of candidness is precisely what I hope for in biographies. The point is not to gawk or merely to satisfy curiosity. Glimpsing the parts of others' lives that are normally hidden allows us to gain a better sense of where our own experiences lie within the space of all possibilities, and - hopefully - to find new strategies or inspiration for dealing with our own problems.

Hawking's life should be inspiring. What he suffered is close to my idea of the worst thing that could happen to someone. Not only did he endure it, he saw positives in it (saying that his physics research was helped by his condition making him more focused), and apparently continued to approach life with enthusiasm and determination. I must admit that I find such strength mystifying. I feel that, in his position, I would have despaired.

Solutions and Other Problems by Allie Brosh (2020-09-24)

"...trying really hard when you don't know what you're doing just happens to be the exact recipe for acting like a fuckin' weirdo" - way too real

Piranesi by Susanna Clarke (2020-09-21)

Even though Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell is one of my favorite novels, I somehow missed the announcement of this book. I only found out about it a few days ago, thanks to a sidebar ad on Goodreads. It was possibly the only occasion in my entire life on which I was happy to see an advertisement.

Reading this feels like retreating into a calm, elegant, orderly universe. I suggest a dark room and classical music.

Midnight Robber by Nalo Hopkinson (2020-09-19)

This is a heavier story than the cover art might lead you to expect, but it's a good one.

Permutation City by Greg Egan (2020-09-09)

...Maria gazed at the blur of codons, and mentally urged the process on – if not straight toward the target (since she had no idea what that was), then at least … outward, blindly, into the space of all possible mistakes.

I loved Egan's Diaspora, and I loved this just as much. Reflections on the nature of consciousness and mind simulation always hook me. If you don't like heavily-idea-driven sci-fi, this book is not for you, but, well, you're missing out. It's a rush of fascinating concepts.

A Crack in Creation by Jennifer A. Doudna (2020-09-07)

In my mind the distinction between natural and unnatural is a false dichotomy, and if it prevents us from alleviating human suffering, it's also a dangerous one.

I really enjoyed the first of the book's two parts, which gives a nice explanation of what CRISPR is and how it works, as well as an interesting window into the process of making a major scientific breakthrough.

The discussion of the ethical concerns is also fairly balanced though not very deep. One thing that comes up here, which always makes me roll my eyes, are calls to hold off on certain research or applications until the "public" can have a "discussion". Who determines when there's been sufficient discussion? It seems like a call for endless hand-wringing, and a futile one at that. But the book does address this to an extent, by discussing the historical precedent of the "Berg letter", which I appreciated.

The Old Way by Elizabeth Marshall Thomas (2020-09-06)

The most interesting aspects of Thomas's description of the Ju/wasi might be the deep-rooted cultural traditions for fostering equality. Individuals feel a need to not stand out, not even by appearing more skilled than others. Food distribution is governed by practices designed to encourage sharing and emphasize the community's connectedness. The society described in this book does not at all sound like one I would wish to live in, but it is fascinating to hear how one long-lived culture found very stable approaches - very different from those of my own culture - to some of the fundamental human social problems.

Monday's Not Coming by Tiffany D. Jackson (2020-08-30)

Engaging and emotionally impactful. I listened to the audio version, which is narrated well. Without being able to flip back and forth between chapters easily it's a bit hard to keep a grip on the timeline - with its headings like "The After" and "Two Years Before the Before" - but that's a minor annoyance; I don't think the chronology is too important.

I had trouble buying into the premise. Would everyone really just go on like nothing had happened when a kid literally disappears from school and social life? But this says more about my background than about the book; as another review notes, several details from the novel match a specific real-world case.

My only definite complaint is that the book could have been shorter without losing anything. I didn't need multiple we were one second away from finding out what was going on, BUT SUDDENLY we were interrupted! scenes.

Maybe You Should Talk to Someone by Lori Gottlieb (2020-08-16)

...at some point in our lives, we have to let go of the fantasy of creating a better past.

This book is three things: a memoir, a set of fictionalized mini-biographies, and a collection of thoughts about therapy and life in general. It's successful as all three.

My favorite memoirs provide an honest look at a person's sufferings and failures. I appreciated Lori's discussion of her intense but repeatedly frustrated desire for a child (thanks to being "desperate, but picky") and her difficulty handling a particular breakup. These kinds of windows into other people's lives are important for helping us develop realistic expectations as to what is "normal" and helping us accept our own and others' emotions.

It's unfortunate (but understandable) that the accounts of her patients had to be anonymized and remixed. They're moving, but you can't know to what extent the breakhroughs she describes are reflective of reality, or idealized to fit a narrative.

Working in Public by Nadia Eghbal (2020-08-14)

We assume that open source projects need to grow strong contributor communities in order to survive.... But this narrative no longer translates to how many open source projects work today.

This book is packed with interesting quotes, stats, and analysis.

My main takeaway is: most open source projects are reliant on an individual or small group of core contributors. The attention of those individuals is a crucial limited resource that needs to be rationed. Pushing a larger number of people to make open source contributions, or expecting maintainers to foster a sense of community participation, can be counterproductive, as it requires the maintainers to spend more time on reviews and discussions of contributions that frequently turn out to have low value.

This makes sense to me. In an enterprise setting, once a team gets beyond a certain small size, adding new people often does not increase productivity. It carries significant training costs (which don't pay off if the people don't stick around - most open-source contributors won't) and coordination costs. I don't know why we'd expect this to be different in the open-source world.

I'm also fascinated by Eghbal's claim that the focus of developer culture is shifting from projects to people, with some developers publishing large numbers of projects or code-related media, and holding influence over fans who follow them personally rather than following any particular project. There's an exciting aspect to this trend: as more developers fund each other on an individual basis (e.g. via Patreon), open source can perhaps be less beholden to corporate interests.

Philosophy of Language by Colin McGinn (2020-08-08)

I decided to try to learn a bit about philosophy of language because stuff I was reading about philosophy of mind kept referring to it. This book was very helpful; I love the format and really appreciate its clarity. I read the original paper after reading each chapter, and generally felt McGinn had already told me most of what was worth knowing about it.

I still don't really see the appeal of philosophy of language, though. What's the point? What are the consequences of favoring one theory over another? Those questions remain unclear in my mind.

Dog on It by Spencer Quinn (2020-07-31)

This was pretty adorable.

The AI Does Not Hate You by Tom Chivers (2020-07-25)

Like the author, I'm sympathetic to, but not really part of, the "rationalist" community. Not many of the ideas discussed here were new to me, but it was interesting to get a bit more historical context about the group.

Ammonite by Nicola Griffith (2020-07-19)

Sometimes, when I read a book for a book club, I only skim the blurb before I start reading it, and come in with some major misconceptions. In this case, that took the form of me reading the entire book under the belief that it had been written last year. Only the date on the author's postscript finally clued me in to the fact that it was published much closer to my own birth than to the present. I'd say it's aged pretty well: apart from overly limited data storage technology, nothing jumped out at me as anachronistic.

Early in the book there is emphasis on the fact that the virus kills all men (or is there? did I just assume that should be salient, because I'm a man?), but that never really matters much to the story. Griffith addresses this in the postscript:

A women-only world, it seems to me, would shine with the entire spectrum of human behavior: there would be capitalists and collectivists, hermits and clan members, sailors and cooks, idealists and tyrants; they would be generous and mean, smart and stupid, strong and weak; they would approach life bravely, fearfully and thoughtlessly. Some might still engage in fights, wars and territorial squabbles; individuals and cultures would still display insanity and greed and indifference. And they would change and grow, just like anyone else. Because women are anyone else. We are more than half of humanity.

That makes sense and leads to a very believable portrayal of a male-free society. Unfortunately, it also means that to make the point, the novel is basically required not to do anything particularly interesting with the premise that there are no men. Science fiction is about asking "what if?" and it's a bit of a let-down when the answer is "well, stuff would be pretty much the same." But entertainment is only one function of literature: the author clearly meant to provoke thought.

And of course, Ammonite is about much more than the men who aren't in it. It has strong fantasy vibes: emphasis on finding one's place in an order steeped in tradition, and in a world suffused with quasi-mystical interconnection. And there's the theme of connecting with one's self and one's physicality. Though I enjoyed the book, these are not themes that resonate with me much.

Mouthful of Birds by Samanta Schweblin, Megan McDowell, Ben Newman (2020-06-29)

Schweblin definitely knows how to write disturbing stories; some of these are misses, but I think some will prove quite memorable, including "Butterflies", "Mouthful of Birds", "Heads Against Concrete", and "The Heavy Suitcase of Benavides".

The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde (2020-06-14)

Actual life was chaos, but there was something terribly logical in the imagination. It was the imagination that set remorse to dog the feet of sin.

I wouldn't say I came away from this with any deep insights about life, but Wilde's writing is delightful.

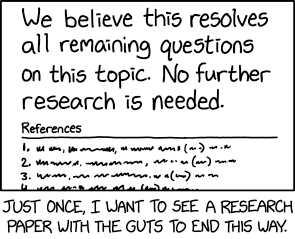

Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus by Ludwig Wittgenstein (2020-06-13)

I was reminded of that XKCD comic while reading the preface, in which Wittgenstein declares:

"...the truth of the thoughts communicated here seems to me unassailable and definitive. I am, therefore, of the opinion that the problems have in essentials been finally solved."

In fact the SEP states that for several years after publishing the book he was "divorced from philosophy (having, to his mind, solved all philosophical problems in the Tractatus), gave away his part of his family’s fortune and pursued several ‘professions’ (gardener, teacher, architect, etc.) in and around Vienna."

He sounds like quite an interesting fellow. To what extent the book actually succeeds at its lofty aim is difficult for me to assess since I couldn’t very often tell what it was saying. This should probably be read alongside, or after, a commentary. The general point seems to be that only statements about the natural world - scientific statements - are meaningful, and stuff like ethics and metaphysics is either meaningless or belongs to a mystical domain we cannot meaningfully discuss. Why one should believe that - even if we overlook the issue, alluded to in the book, that that claim would itself seem to be meaningless by its own standard - is unclear to me.

This Is How You Lose the Time War by Amal El-Mohtar, Max Gladstone (2020-06-04)

Her pen had a heart inside, and the nib was a wound in a vein. She stained the page with herself.

What this book offers: eloquent romantic exchange

What not to expect: much plot; precise time-travel mechanics or worldbuilding

The Character of Consciousness by David J. Chalmers (2020-05-31)

...the structure and dynamics of physical processes yield only more structure and dynamics, so structures and functions are all we can expect these processes to explain. The facts about experience cannot be an automatic consequence of any physical account, as it is conceptually coherent that any given process could exist without experience. Experience may arise from the physical, but it is not explained by the physical.

I appreciated the first five chapters the most. Chalmers defends the existence of the “hard problem” against unsatisfactory attempts to deflate it, develops a taxonomy of possible solutions, and provides commentary on relevant scientific issues. The penultimate chapter, which uses a discussion of The Matrix to provide thoughts on the problem of skepticism in general, is also quite interesting.

I found many of the other chapters difficult to follow, likely because I lack background in the philosophy of language. The connection of the highly technical discussions to the “big picture” was often unclear to me.

Blindsight by Peter Watts (2020-05-31)

I first tried to listen to this a few years ago but found it very off-putting. I’m glad I gave it a second chance; the protagonist is a more complex and emotionally interesting character than he seems at first, and the ideas explored in the novel are very fascinating.

Illusionism by Keith Frankish (2020-05-16)

I picked up this book to try to gain a better understanding of a position that seemed blatantly, self-evidently false to me. That’s pretty much still my opinion, though it’s possible I’m interpreting the idea of illusionism as a slightly more radical claim than Frankish intends - but if so, I don’t understand how it differs from the more ‘conservative’ physicalist views he wishes to distinguish his view from. Regardless, these were thought-provoking papers. I really love the format of presenting a variety of responses to a target article - I wish this were more common.

The First Fifteen Lives of Harry August by Claire North (2020-05-13)

Really creative and fascinating premise paired with good writing.

The View from Nowhere by Thomas Nagel (2020-05-05)

Too much time is wasted because of the assumption that methods already in existence will solve problems for which they were not designed; too many hypotheses and systems of thought in philosophy and elsewhere are based on the bizarre view that we, at this point in history, are in possession of the basic forms of understanding needed to comprehend absolutely anything.

Objectivity of whatever kind is not the test of reality. It is just one way of understanding reality.

Nagel contemplates our capacity to try to step outside ourselves and form an objective conception of the world, presenting this ability and its inescapable limitations as the source of some of our most difficult philosophical problems related to knowledge, personal identity, free will, and ethics. His discussion reveals analogies between those areas that hadn’t occurred to me before.

Jagannath by Karin Tidbeck (2020-05-03)

A collection of twisted, fascinating stories. My favorite is “Rebecka”, a disturbing take on life in the presence of an undeniable deity. The first (“Beatrice”) and last (“Jagannath”) are also particularly good.

In the Night Garden by Catherynne M. Valente (2020-04-27)

…her absence stalked the house like a hungry dog. The hole where she had been took up space at our dinner table, it sagged and slumped in the musty air, it ate and drank and breathed down all of our necks. … But still, the hole answered the bell when he rang, and he had to scurry to bed with his head down to avoid looking it in the eye.

I really enjoyed the use of short, interleaving segments told from a large number of characters’ points of views. Valente’s writing and world-building set the perfect mood for a dark - but not bleak - fairy tale.

Radical Acceptance by Tara Brach (2020-03-30)

Facing fear is a lifelong training in letting go of all we cling to—it is a training in how to die.

I’m not really in the target audience of this book. Although there are chapters about desire and fear, most of the book is about how to face being disappointed in yourself. I’m more interested in how to face being disappointed in my circumstances. It’s also heavy on mysticism and spirituality, and emphasizes that the essential nature of humans is goodness. That seems like wishful thinking.

Like a lot of self-help books, this one paints its core idea as the sort of Ultimate Answer to dealing with (albeit not exactly fixing) all of life’s problems. It tries to hold the line that we should accept everything about ourselves non-judgmentally, even our judgmental tendencies, but it’s hard to escape the implication that failing to do so is therefore judgment-worthy. As an all-encompassing philosophy it seems dubious. But viewed as one set of psychological tools for handling problematic feelings, some of it seems useful. It's finally convinced me to give meditation a shot, at least.

Map and Territory by Eliezer Yudkowsky (2020-02-28)

But if you can’t say “Oops” and give up when it looks like something isn’t working, you have no choice but to keep shooting yourself in the foot. You have to keep reloading the shotgun and you have to keep pulling the trigger. You know people like this. And somewhere, someplace in your life you’d rather not think about, you are people like this.

Being a collection of blog posts, this is somewhat disjointed, and the level of assumed background knowledge seems to vary significantly among chapters. But it’s a nice grab-bag of information about biases and Bayesian reasoning.

The Constitution of Liberty by Friedrich A. Hayek (2020-02-27)

Though most people regard as very natural the claim that nobody should be rewarded more than he deserves for his pain and effort, it is nevertheless based on a colossal presumption. It presumes that we are able to judge in every individual instance how well people use the different opportunities and talents given to them and how meritorious their achievements are in the light of all the circumstances which have made them possible. It presumes that some human beings are in a position to determine conclusively what a person is worth and are entitled to determine what he may achieve.

The key concept in this book is the “rule of law.” For me that term merely calls to mind the question of whether government officials must adhere to the law like everyone else. But Hayek uses a much more demanding and more interesting definition.

In his view, rule of law requires that legal rules be “general, equally applicable, and certain.” Laws which privilege a majority or discriminate against a minority do not meet this standard, even if enacted by honest democratic processes. Laws which give significant discretionary power to government officials also undermine the rule of law - when the legality of an official’s action is determined by whether they were allowed to take that action by law, rather than whether they were required to take that action by law, the effect for citizens is that the rules are uncertain and unequally applied. And this means that citizens are subject to “the arbitrary will” of others. This is a fascinating axis for evaluating government policy, one with important differences from the more commonly discussed axes of freedom vs central planning or individualism vs collectivism.

The Republic by Plato (2020-01-27)

...if a city were composed entirely of good men, then to avoid office would be as much an object of contention as to obtain office is at present...

The Republic discusses some interesting topics, but I’m not sure there’s much to be gained by reading it today, compared with reading more recent philosophers. Plato’s reasoning seems very sloppy by modern standards; the challenge I felt while reading this was generally not “where’s the mistake” but rather “why would I believe any of these premises or inferences in the first place."

Gideon the Ninth by Tamsyn Muir (2020-01-24)

I listened to this for a book club. I wasn’t expecting it to be my kind of thing at all, and the first couple of hours only seemed to confirm that expectation. But at some point I started really enjoying it; it’s a lot of fun, and achieves some real emotional impact at points.